Cover Story

8 |

drinkanddrugsnews

| July/August 2016

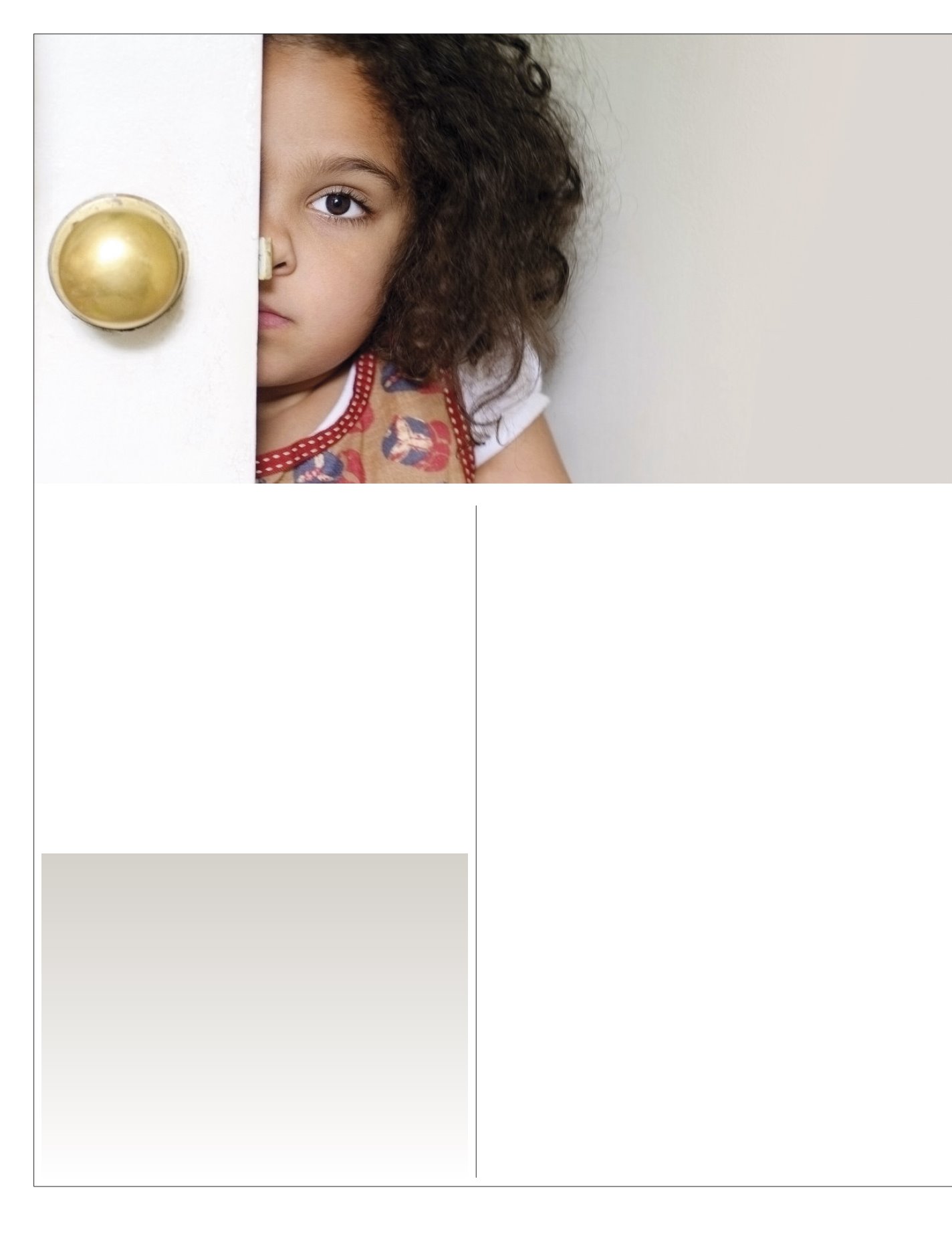

E

nduring adversity in childhood presents both challenges and

opportunities in later life. But it is known that experiencing significant

trauma in childhood considerably increases the risk of misusing drugs

and/or alcohol. Research tells us that our early life experience

programmes the brain and the body for the environment that it

encounters. So a calm, nurturing childhood is likely to orientate a child to thrive in

most conditions, while a highly stressful, bleak, abusive one will predispose it to

conditions of anxiety, insecurity and chaos. What is interesting is why some

individuals do not suffer from addictive behaviours and mental health problems,

while others do.

Abuse and trauma in childhood take many forms and are categorised under

physical, emotional and sexual harm. Much under reported but very common, is the

impact upon children of a low level but pervasive parental vacuum, where there is a

significant absence of real parental engagement. This can be because the parent is

preoccupied with their own problems, such as depression or mental illness; or it can

be because they are dangerously immature, and therefore more concerned with

having their needs met than nurturing their child and overseeing their teenager.

Even more damaging to a child can be the chronic recurrent humiliation of

emotional abuse – being told that you are useless or not good enough.

The term ‘child’ refers to pre-birth from the time of conception, through to the

age of 18. Some parents consider that their role as vigilant and nurturing carers

ends when their child reaches ten or 12 years. But young people require love, care

and actual parenting until they are adults themselves – and beyond. Many young

people find themselves becoming increasingly involved in drug and alcohol

misuse, but this can be overlooked, minimised or rationalised by a parent until it

is too late.

In my 35 years of practice in this field, the most common factor I have come

across when talking to those suffering from substance misuse and mental health

problems, is that there has been some very significant trauma in their lives that

they have not fully revealed before, and certainly not recovered from.

Research bears out that those who misuse drugs or alcohol have so often been

victims of sexual abuse. Such victims suffer post-traumatic stress disorder leading

to poor coping skills, anti-social behaviour, depression, anxiety, low self-esteem and

problems in forming trusting relationships. Substances can be used to cope with or

escape the trauma and memories of sexual abuse, and as a way to reduce a sense

of isolation and loneliness. They become a form of self-medication, to boost

confidence and improve self-esteem, or a form of self-destructive behaviour and

self-harm. Either way, an individual has raised the red flag asking for help, and as

practitioners we need to respond quickly.

A significant percentage of those who have a substance misuse problem also

have a recurring mental disorder such as depression, anxiety and/or post-traumatic

stress disorder. Process addiction, such as gambling, disordered eating and internet

addiction, has been found widely in those who report childhood sexual abuse. Of

course one of the difficulties of this kind of abuse is the difficulty for survivors in

acknowledging and reporting it, and it is also difficult for caregivers to identify.

Research confirms that the more adverse childhood experiences encountered,

and the higher the types of stress, the greater the odds are of an individual

suffering with later life addiction. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study

included 17,000 participants and found multiple relationships between severe

childhood stress and all types of addictions, including under and over-eating. These

adverse experiences included emotional, physical and sexual abuse, neglect, and

living in a house where domestic violence had taken place. Compared to a child

with no adverse childhood experiences, one with six adverse or more experiences is

nearly three times more likely to become a smoker as a child; a child with four or

more is five times more likely to become an alcoholic and 60 per cent more likely to

become obese. A boy with four or more ACEs is 46 times more likely to become an

IV drug user in later life than one who had no severe childhood experiences.

An adult survivor of child sexual abuse cannot be categorised easily. There are

complex dynamics at play and deep trauma at work. Generally speaking, adults will

normally have one or two outlooks on life after such abuse. They will either collapse

or they will attempt to rise above the abuse. The collapsed outcome is an adult who

has easily recognisable symptoms and problems that stop them from being

functional in more than one area of their life. They have depressive, addictive or

victim status personas, and require ongoing medical and other assistance to cope.

The second outcome often includes those who dissociate from the abuse by

‘soldiering on’ and maintain, for some time, an intact functional life in work and

‘Much under reported but

very common, is the impact

upon children of a low level

but pervasive parental

vacuum, where there is a

significant absence of real

parental engagement.’

Behind