Basic HTML Version

alcohol for comfort, while others couldn’t stand the sight of it. Some

perpetrators seemed to enter rages fuelled by drugs or alcohol,

while one or two were described as even worse when sober. ‘You

mention the word monster… that’s what I call my son – the

monster,’ a mother said.

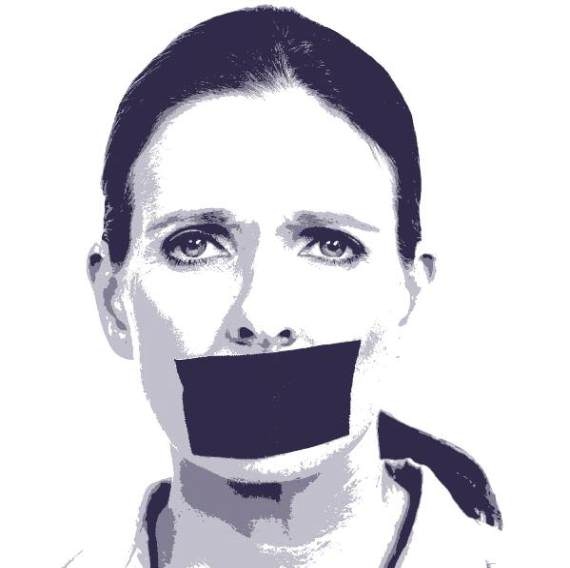

All these factors contributed towards a profound

shame felt by many parents who did not feel comfortable

sharing their experiences with professionals, and

sometimes even friends and family. ‘You can’t talk to your

own family – I get too upset. My twin sister doesn’t know

my son is a drug addict – he’s been an addict for 20

years and she doesn’t know. I want to tell her but I don’t,

I feel ashamed.’ This sense of shame and stigma was

also reinforced by some of the reactions parents got

from people who should have been potential sources of

support, with one mother being told ‘it’s because you’re a

one-parent family’ by one of her friends.

With all this stigma to face, it’s unsurprising that many

parents didn’t immediately ask for help, but instead did

their best to deal with the situation themselves. Even

when help was available they were often not aware

of the network of excellent family support groups

that exist around England for families affected by

drugs and alcohol. ‘I didn’t know there was

support for us… I was talking to a friend and

the friend told me that there was support out

there for me, which I knew nothing about,’ a

parent reported.

Unfortunately, when parents did make that

step and ask for help, many of the responses

they received were not satisfactory. A mother

told us that there ‘seemed to be a problem with

social services when it’s the parent or family

requiring help, rather than the child. There

seems to be some sort of mental block where

they can’t understand, or don’t want to

understand, that possibly the family are not able

to deal with the child.’

We summarised everything parents told us in

the report

Between a rock and a hard place

and

made a series of recommendations for policy

makers which we believe can improve

recognition of CPV and, crucially, the support available for parents. You can read

more of the moving, but often inspiring, stories the parents shared at

www.adfam.org.uk/news/265

and if you’d like to know more about the project

email me at o.standing@adfam.org.uk or call 020 7553 7656.

Oliver Standing is policy and projects coordinator at Adfam

Adfam and DDN are holding a ‘Families First’ conference for family members and

professionals on 15 November in Birmingham. Details at www.drinkanddrugsnews.com

In the last quarter of 2011

I travelled around England

with the director of domestic violence agency AVA, Davina

James-Hanman, meeting parents whose children had

drug and alcohol problems. This in itself was not

unusual – many of Adfam’s projects are based on

focus groups and consulting families affected by

substance use. What made this project different,

however, was that these parents were victims of

domestic abuse perpetrated by their children.

‘I’ve had knives at my throat off him,’ one

mother told us. ‘He said to me, “you better move

now ’cos I’ll use it”, so I said, “do me a favour and

do it because I can’t take it anymore, you’re

destroying me”.’ Like victims of intimate partner

violence (IPV), though, victims of child-parent

violence (CPV) suffer more than acts of physical

violence – domestic violence is usually manifest as

a process of coercive control where the perpetrator

uses emotional, psychological and sometimes physical

abuse to exert power and control over a victim.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, the experiences of

victims of CPV mirrors those of IPV in their breadth. ‘My

experience is… to do with mental harm,’ another parent

told us. ‘He has just damaged me so much, I am so

tired that I wonder sometimes how I can keep going.’

Many parents reported a common theme of being

worn down by their children, bullied, deliberately

targeted when at their weakest and financially

exploited. ‘I’ve had text messages saying he’ll have

his legs broken if we don’t pay £500 by this Friday,

and we’ve got ourselves into serious debt,’ one

parent told us.

For anyone to deal with this is, of course,

immensely hard, but consider the two extra factors

at work here. Firstly, the perpetrator of the abuse is

the child of the victim. This reversal of the normal

power relationship touches on a major taboo in

most societies, which generally assume that the

parent has control over the actions of the child and

that any behavioural issues are the result of lax or

inefficient parenting.

Even if a parental victim reaches a point where he

or she attempts to sever ties with the perpetrator, they are still a parent responsible

for their child in the eyes of society, the law and, often, themselves. One mother we

spoke to regretted the firm stance she’d taken – ‘I wish I hadn’t thrown my son

out… that goes against the grain… a mother to chuck her son out’.

Secondly, drugs and alcohol complicate the picture even more. The relationship

between substances and domestic violence can be very complicated, reflected in

the variety of stories shared with us. Some parents had themselves turned to

12 |

drinkanddrugsnews

| October 2012

Families |

Child-parent abuse

www.drinkanddrugsnews.com

‘My twin sister doesn’t

know my son is a drug

addict – he’s been an

addict for 20 years and

she doesn’t know. I want

to tell her but I don’t...’

More support – and understanding – is needed for victims of violence

and abuse perpetrated by their children, says

Oliver Standing

The last taboo