Basic HTML Version

www.drinkanddrugsnews.com

October 2013 |

drinkanddrugsnews

| 21

Soapbox |

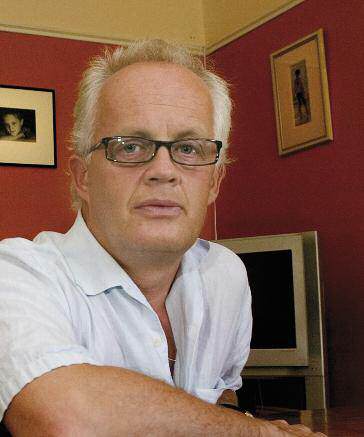

Neil McKeganey

Soapbox

DDN’s monthly column

offering a platform for

a range of diverse views.

THE

BIG

QUESTION

Is drug prohibitionhelping

or hindering recovery,

asks

NeilMcKeganey

Professor Dame Sally Davies, the chief medical

officer for England, recently joined a growing

chorus of voices in the UK calling for drugs to be

treated as a health rather than a criminal

justice issue.

Earlier this year the British Medical

Association published its

Drugs of dependence

report, which included a similar call, and in May

the Royal College of General Practitioners voted

in favour of decriminalising all illegal drugs at

its 18th national conference on managing drug

and alcohol problems, advocating that drug use

should be seen first and foremost as a health

issue. It’s a debate that has been aired recently

in

DDN

, with correspondence between Dr Chris

Ford and Anna Soubry MP, among others.

The belief underpinning these calls is that

somehow drug users’ needs, including their

recovery needs, are being impeded as a result of

the drug laws, and that only by overturning

those laws will it be possible to fully meet these

needs. What is the evidence that their recovery

is being hampered by so-called ‘prohibitionist’

drug laws? One way in which this might be

occurring is if individuals are less willing to

contact drug treatment services as a result of

tougher drug laws.

Contrary to what you might expect, some

countries with the most liberal drug policies

have the lowest proportion of drug users in

treatment. In Portugal, where drugs were

decriminalised for personal use in 2002 and

treatment has been promoted in preference to

prosecution, only 14.2 per cent of problematic

drug users are in contact with drug treatment

services. Similarly, in Italy, which has a policy of

dealing with drug possession offences with

administrative rather than criminal justice

penalties, only 14.6 per cent of problem drug

users are in contact with treatment services.

Both of these countries have a lower level of

contact with drug treatment services than either

Sweden, known for its zero tolerance drug

policies, or the UK, where heroin and cocaine

attract the highest criminal justice penalty.

On the basis of these data it would appear

that there is no simple association between

restrictive drug laws and the proportion of

problem drug users receiving drug dependency

treatment. As a result it cannot be simply

asserted that the drug laws are hindering

people’s access to treatment.

Recovery, though, is about more than the level

of contact with drug treatment services. One of

the challenges that drug users often face in their

recovery has to do with avoiding the ‘cues’ that

remind them of their former drug use. It is for this

reason that recovering addicts often try to move

to a new area as a way of reducing their exposure

to the people and the places that are most closely

associated with their past drug use.

In the case of recovering alcoholics,

reducing their exposure to alcohol is made that

much more difficult by the near ubiquity with

which the product is available within our

culture. In contrast, heroin is much less

available and the recovering addict has to work

less hard to avoid being exposed to the drug.

One of the ways in which the drug laws may

actually assist individuals in their recovery is

through reducing the visibility and accessibility

of the drugs involved.

There are other ways in which the fact that

some drugs are illegal might impact adversely

on individuals’ recovery, one of which has to do

with stigma. There is no doubt that individuals

dependent upon illegal drugs are highly

stigmatised – but so too are alcoholics. The

stigma felt by those who are drug or alcohol

dependent may have less to do with the legal

status of the drugs than the negative

judgements around the individual being seen to

be ‘out of control’ in their behaviour.

Securing employment is an important part

of the process of sustaining an individual’s

recovery and one that can be adversely affected

by negative attitudes on the part of employers.

We know that many employers are reluctant to

employ a recovering drug user and that as a

result, the individual’s recovery is made that

much harder. However, the negative

judgements of employers may have more to do

with the perception of the drug user as

unreliable or untrustworthy than the illegality

of the drugs involved.

There will be many occasions though when a

recovering drug user’s chances of securing

employment will be adversely affected as a result

of them having a criminal record. This is a

problem that can be dealt with without the need

to overturn the drug laws through, for example,

expunging drugs convictions where the individual

is seen to be demonstrating a sustained

commitment to recovery.

In the calls to treat drug use as a health

rather than a criminal justice issue there is an

assumption that the drug laws are having an

adverse impact on the delivery of health-

related support and that as a result society

should choose between viewing drug use as a

health or a criminal justice issue. The fact that

certain drugs are illegal may actually help an

individual’s recovery journey and it is certainly

not the case that countries with the most

liberal drugs laws are necessarily the best at

providing accessible drug treatment services to

dependent drug users.

Instead of viewing drug use as either a

health or a criminal justice issue there is a

strong case for retaining both elements in how

we are tackling our drug problems; ensuring

that those in recovery are assisted in every way

possible, including by reducing the availability

and accessibility of illegal drugs on the streets.

Professor Neil McKeganey is at the Centre

for Drug Misuse Research, Glasgow