and clearly didn’t believe in recovery, so we decided

we’d set up our own little support group.’

Does he feel that the value of therapeutic

communities has been properly recognised, or is

there still a way to go? ‘No, there’s a very long way to

go, and unfortunately I think the track we set out on

was the wrong one. One of the major mistakes

therapeutic communities made was to accept that

they were about drug treatment. That effectively

made them part of the health service, measured by

those kind of randomised control trials that are very,

very difficult to implement in such a complex

intervention.’

What such communities are really about is

people learning to live and behave in a different way,

he believes, and helping each other to do that in a

structured environment. ‘In some respects we’ve

hamstrung ourselves into being simply about drug

treatment, and I don’t think the approach is simply

about that. I think it’s much broader.’

Is it too late to reverse that now? ‘I think so,’ he

says. ‘One of the problems therapeutic communities

and other residential agencies have faced over the

last 20 or 30 years is the hijacking of some of the

radical psychiatry notions about closing down big

psychiatric institutions and moving people into the

community. Right-wing governments – like Margaret

Thatcher’s – hijacked that notion because they saw

an opportunity to save huge amounts on health

costs, not because they thought people could be

cured in the community but because they thought,

“We can close down this massive loony bin and sell it

to Tesco”.’

That bred a notion of ‘residential bad, community

good’ that still exists, he argues. ‘But I think we’re

beginning to move out of that and recognise that it’s

not really about residential and non-residential, it’s

about treatment dosage. Some people will need a

higher level of treatment intensity, a bigger dose,

and the most effective way of delivering that is

probably in a residential setting.’

So how does he feel about his imminent

retirement? ‘I think it’s time, really, although I’m

going to retain some of my responsibilities. Looking

back, the major milestone for me was being made

Phoenix Futures’ first – and only – honorary

graduate. That was far more important to me than

my MBE or other appointments over the years.’

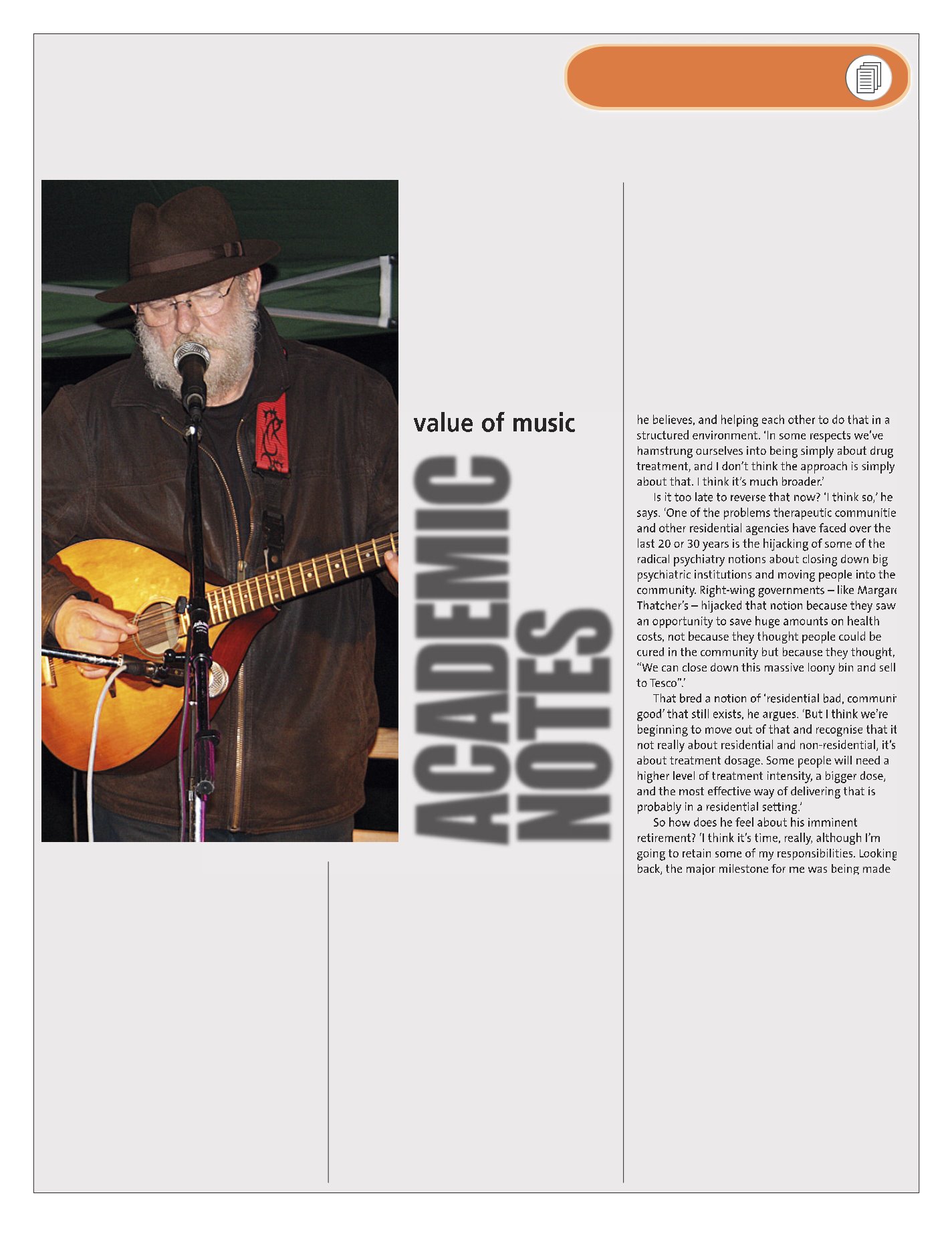

His retirement will also give him the time to

indulge his other passion, music, especially with his

band Running wi’ Scissors. ‘I love playing music, but I

kind of came out of it for a number of years and

didn’t play at all, because for me my involvement in

it was associated with my involvement in drugs. I

was frightened to play music, I suppose.’

The value of music and other creative activities in

people’s recovery is something else that remains

hugely under-appreciated, he says. ‘Music and drama

and dance are often seen simply as ways of filling

residents’ time – something they can do in the

evenings. I think it’s much more important than that.

We know from studies that playing music fires off

synapses in the brain that don’t otherwise fire, so it

has a profound effect on people’s thinking and self-

esteem. That’s a really interesting area to explore.’

16 |

drinkanddrugsnews

| November 2015

Profile

Read the full interview online

Drug sector

veteran Rowdy

Yates talks

to

David Gilliver

about the value

of therapeutic

communities, and

the therapeutic

value of music

AcAdemic

notes

could look at residential rehab much more closely

and favourably than we do,’ he says. ‘We’ve had 20

years of thinking that residential treatment is

profoundly expensive and therefore a last resort.’

Much of the research comparing residential and

non-residential models ‘doesn’t compare like with

like’, he argues. ‘They’ll include the accommodation

costs in the residential side of the equation, for

example, but not in the non-residential side. I can

understand why they do that, but the truth is that

the majority of people receiving long-term

methadone maintenance are probably also receiving

housing benefit, so their accommodation is still

costing the state.’

He came into the field in the late 1960s via his

own heroin use and a belief that if people wanted

effective support they’d need to create it themselves.

‘A group of us ex-heroin addicts had been attending

Alcoholics Anonymous, which at that time was

about the only game in town. Drug dependency

units, as they were known, were prescribing heroin

‘IT’S KIND OF SCHIZOPHRENIC FOR ME BECAUSE ONE

DAY I’M AN ESTEEMED ACADEMIC DOING MY

PRESENTATION AND THE FOLLOWING DAY I’M UP ON

STAGE PLAYING,’

says Rowdy Yates of last month’s

annual conference at the San Patrignano community

in Italy.

A passionate commitment to both therapeutic

communities and music has defined his 46 years in

the field, and although he resigns his post as senior

research fellow at the University of Stirling at the

end of this year, he’s staying on as president of the

European Federation of Therapeutic Communities

(EFTC) until 2017. And the community of San

Patrignano (

DDN

, March 2014, page 8) is a shining

example of what the sector can achieve, he believes.

‘It’s great,’ he says. ‘I mean, you’re talking about

1,500 people – it’s the biggest rehab in the world,

really, and there’s a very strong, therapeutic

community emphasis on self-help, self-governance.’

Is it a model that we could perhaps look at a little

more closely in this country? ‘My view is that we