For the stories behind the news

February 2016 |

drinkanddrugsnews

| 9

see alcohol and ageing on the agenda across a

number of cross-care areas, such as dementia,

retirement, social isolation. Alcohol use

doesn’t happen in a vacuum.’

The programme is also advocating for the

needs of older people to be specifically

highlighted in existing government strategies,

in order to raise the issue in professional and

commissioning circles. ‘Up until now only the

Wales and Northern Ireland alcohol strategies

particularly reference the needs of older

adults,’ says Breslin.

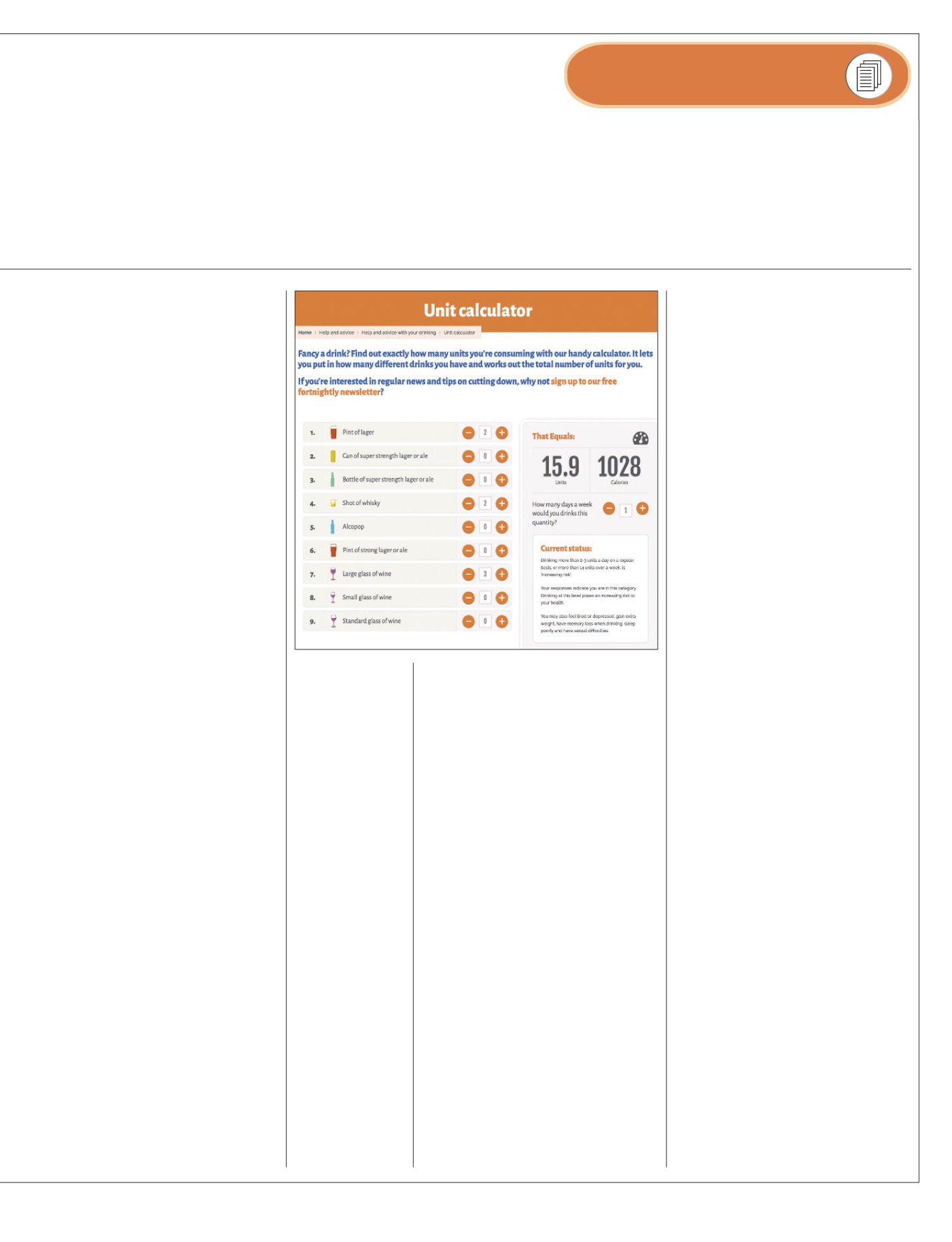

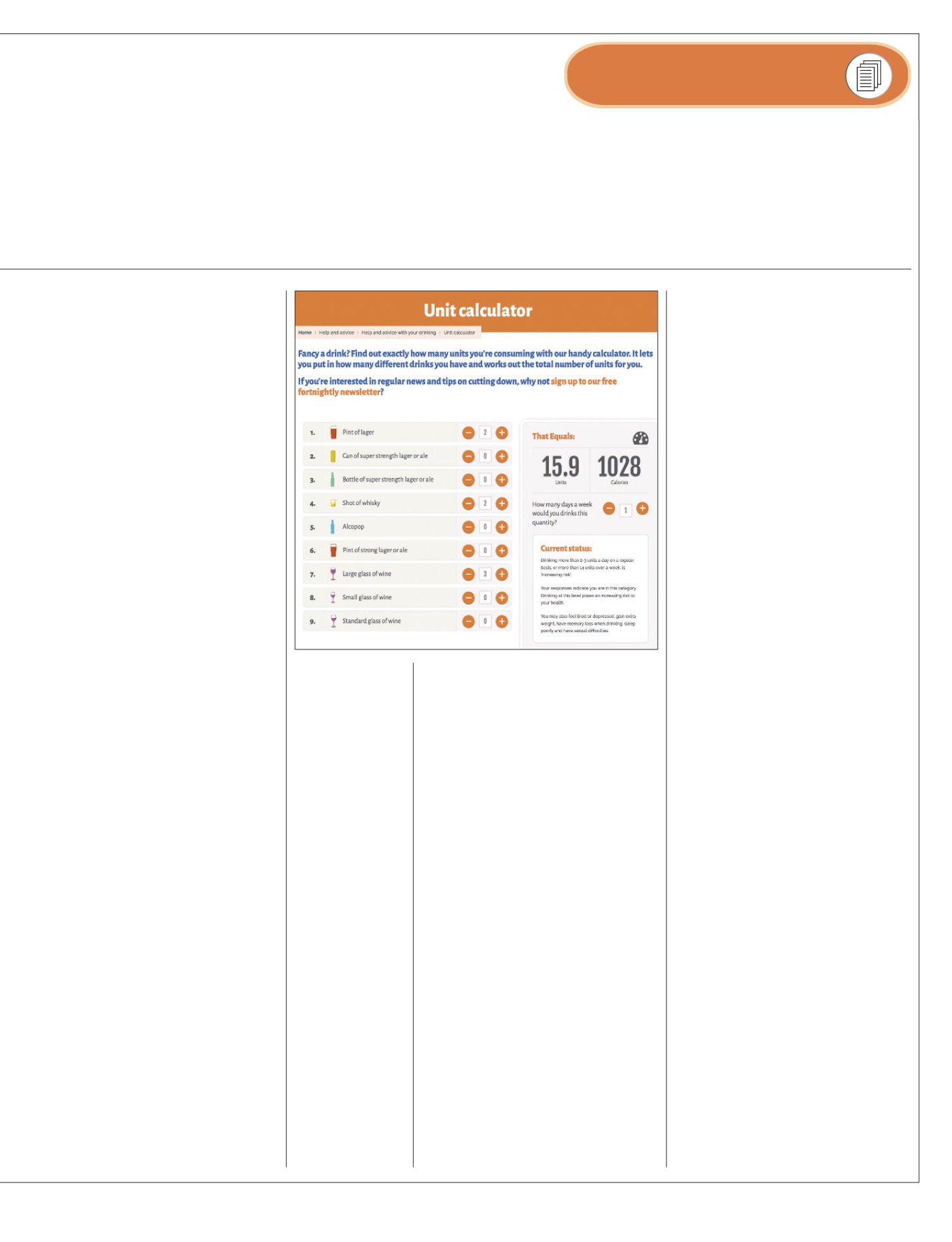

One of the major issues identified by the

report is a widespread confusion and lack of

awareness around units and guidelines. Will

the recent revisions go some way to rectifying

that or is there still a lot more to be done to

get a clearer message across? ‘In our report

nearly three quarters of respondents were

unable to correctly identify recommended

units,’ she says. ‘Hopefully the new guidelines

are a good starting point and easier to digest.

However for many people even the concept of

“units” is difficult to grasp and we may need

to work together to find better ways to

communicate the message. It would be

helpful to provide resources that allow people

to self-measure and start to understand their

own consumption better.’ The drinks industry

also needs to share a responsibility in getting

the message across, she stresses – they may

have put unit information on labels but it

‘could be a lot bigger’.

As older people have been drinking for

longer, the harm becomes accumulative, she

points out, although the fact that over-50s are

far from a homogenous group is itself a

challenge. ‘You could have an extremely fit

and healthy 73-year-old, versus a 52-year-old

with multiple health issues. We think more

discussion and exploration is required in

relation to the guidelines and how we provide

nuanced age-specific advice.’

There’s always been a strong anti-‘nanny

state’ feeling in the UK, however, and many

are likely to say, ‘If they haven’t got much else

in their lives let them enjoy a drink – why take

that away?’

‘The “nanny state” backlash is certainly

something we’re prepared for and we saw this

very much in the recent revision of the alcohol

guidelines,’ she says. ‘However we believe that

older people in particular do play an active role

in their own health and wellbeing, and given

the right information make healthier choices.

How alcohol affects us, particularly as we age,

is something most people would want to know

about in order to make this choice, in the same

way they would take care of other health areas.’

Assuming that older people don’t want to

make healthy choices or live active and

healthy lives is an ageist approach, she argues,

adding that when they do access alcohol

treatment they tend to have better outcomes

– the problem is that they’re less likely to

engage with treatment in the first place.

‘Assumptions that people are too old to

change are unhelpful and actually quite

discriminatory,’ she states.

If the aim is to help people experience a

better quality of life in their later years, a key

starting point is ‘clear and credible information’,

she stresses. ‘Many people identified positive

reasons for alcohol use such as socialising and

relaxation, and these are important factors for

people as they age. We’re not telling people not

to drink – we’re highlighting what the

particular risks are for older people and proving

advice and information.’

People have to be motivated to improve

their health, however. If someone is lonely,

perhaps bereaved, and feel they have little to

live for they may well know they’re doing

themselves harm but think, ‘So what?’What,

realistically, can be done to counter that?

‘Of course major life transitions such as

bereavement and retirement can be a trigger

for increased alcohol use, and people may feel

that there’s little in their life to change for. In

our direct engagement and support service,

where we work with people over 50 who are

already drinking problematically, our

philosophy is that it’s our job to help people

find the motivation that will help them make

that change. Very often the first stage of

engagement is about relationship building

and dealing with practical issues.’

The problem, she points out, is that it’s

resource- and time-intensive. ‘We are very

lucky to be funded so we can work in this

way,’ she says. ‘What can happen with busy

generic addiction and social work services is

resources may be stretched, and if an older

person – on the face of it – is not showing

motivation to change, resources may be

allocated elsewhere. We know that it takes

time, repeated home visits, and lots of

patience for someone to start to find their

own drive for making a change, and this is the

model we adopt.’

Equipping people with social supports and

coping strategies – ‘resilience interventions’ –

is also vital, she says, so that when they do

experience difficult life changes they are

better able to cope without turning to alcohol.

The report says that what’s needed is an

‘age-nuanced’ approach – what would some of

the elements of that look like? ‘At a wider level

there needs to be a multi-agency approach to

ensure older adults don’t fall through the net,’

she says. ‘Frontline staff and practitioners

should receive training that specifically

challenges stigma and attitudes, whilst

equipping people to better recognise and

respond to older people who may be drinking.’

Among the best-placed people to step in

are health professionals, particularly GPs, as

they’ll usually be the ones older people have

the most regular dealings with. What can be

done to raise awareness among them, and

help them spot any warning signs? ‘Health

professionals have more and more demands

on their time, but better alcohol screening of

patients is a good starting point and in some

areas this is already offered. If older patients

are re-presenting with issues such as low

mood, sleep disorders, stomach problems,

then alcohol use may be a contributing factor.

‘It also may be the case that whilst people

are not drinking at particularly high risk levels,

they are experiencing some health

implications due to age-related changes,’ she

continues. ‘It’s important for community

agencies to work closely together so that GPs

have an easy and accessible referral route

when they do identify someone.’

‘If the aim is to

help people

experience a

better quality of

life in their later

years, a key

starting point is

clear and credible

information.’

Unit calculator at

Alcohol Concern.