Basic HTML Version

T

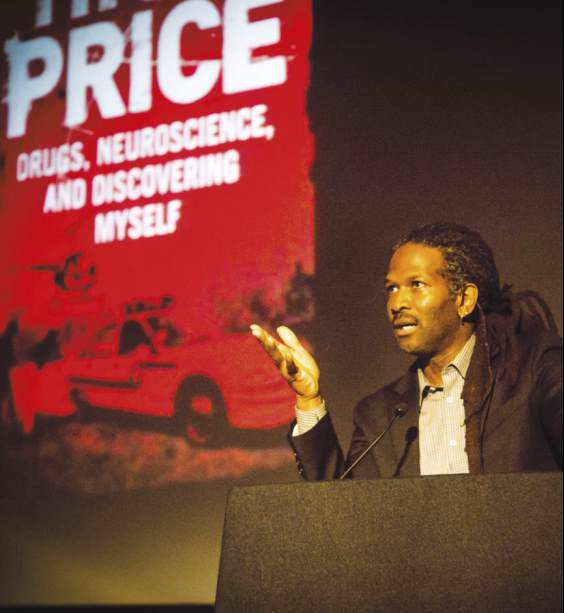

he fervour around crack cocaine reached such a level of hype in the US

in the 1980s, neuroscientist Dr Carl Hart told the 2014 HIT Hot Topics

conference, that at one point black civil rights activists teamed up with

the Ku Klux Klan to combat America’s new Public Enemy No.1.

In 1989 the KKK launched the ‘Krush Krack Kocaine’ initiative, to rid the

streets of Lakeland, Florida of crack dealers. People selling crack were legitimate

hate targets at the time – they’d been described by Jessie Jackson, the Democrat

civil rights activist and Baptist minister, as ‘death messengers’ and ‘terrorists’.

Incredibly, the KKK initiative was ‘welcomed’ by the local National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People.

Crack hit the black community hard. Around 80 per cent of those convicted for

crack offences were black. Harsh new anti-crack laws introduced by President

Ronald Reagan meant that those caught with crack received prison sentences up

to 100 times more severe than for the powder form of cocaine, more commonly

used by white Americans.

Dr Hart became curious about a drug that had so damaged his community in

Miami. He wanted to know more about the drug being mentioned in such fearful

tones by his heroes Gil Scott-Heron and Public Enemy. Dr Hart decided to leave

his job in the US airforce, where he had spent time based over here in Swindon,

and returned to the US to study neuroscience in order to understand crack’s

effect on people’s minds and bodies.

The subsequent research he conducted into the psychology of crack cocaine

use has since become famous. What he found blew holes in the accepted

narrative – that crack cocaine was an entirely new drug that transformed addicts

into mindless zombies intent on violence and getting their next fix. Hart’s

experiments, where crack users were given a choice between $5 and a rock of

crack, found that half the time, these ‘crack addicts’ went for the money. In other

words, they made rational decisions.

‘A small amount of money was enough to shift their drug-taking behaviour. This

made me rethink the crack narrative,’ said Hart. A similar experiment he conducted

among crystal meth users yielded the same kind of results – the drug users did not

blindly lunge for the drugs. ‘I realised that the vast majority of people who use this

drug don’t have a problem. Look at Rob Ford. He could use crack and be mayor of

Toronto. He was a jerk, but he could use crack and be mayor.’

Dr Hart said exaggerations around crack and crystal meth – that they cause

brain damage, obliterate rational thought and are uniquely novel compounds – are

perpetuated more by design than by accident.

‘The public has been misled about drugs. Why is this? It serves a function. It

allows us to target people who we don’t like. We can’t say we don’t like black

people, but we can say we don’t like an activity they are involved in, such as

taking crack. This narrative helps to avoid dealing with the real problems of the

poor, that if we get rid of crack, we don’t have to talk about bad education, bad

housing and so on.’

16 |

drinkanddrugsnews

| December 2014

Conference |

HIT – Hot Topics

www.drinkanddrugsnews.com

This year’s HIT

Hot Topics

conference delved

into neuroscience to challenge

our perceptions of drugs and drug

taking.

Max Daly

reports

IN

MIND

AND

BODY