Basic HTML Version

August 2013 |

drinkanddrugsnews

| 15

www.drinkanddrugsnews.com

Tobacco |

Harm reduction

Where to with tobacco policy?

Harm reduction is central to current tobacco policy in England. This will be

welcome news to those in the drugs field who feel rather beleaguered and

browbeaten by the drugs recovery agenda.

The history of tobacco harm reduction is tied in with the development of NRT. In

1990 there were only three NRT products, all prescription-only. Pharmacy sales

started in 1991, expanded to all products by 2000, and since 2009 all NRT products

have been on general sale. Initially NRT was only indicated for abrupt quitting, and

later extended for people who wanted to cut down more gradually before stopping.

But in 2009/2010 the MHRA agreed it could be used for harm reduction, including

temporary abstinence and a reduction in smoking with no intention to quit.

The Department of Health’s 2011 tobacco control plan committed to

encouraging tobacco users who cannot quit to switch to safer sources of nicotine

and to encourage manufacturers of safer sources of nicotine to develop new types

of nicotine products. In 2012 the Cabinet Office’s behavioural insights team – the

so-called ‘nudge unit’ – urged the use of e-cigarettes.

The most recent piece of the story is the work of the National Institute for Health

and Clinical Excellence (NICE) which gives a strong endorsement for tobacco harm

reduction for people who do not wish to quit smoking altogether, and for people

who want to quit smoking but are unable or unwilling to quit using nicotine. The

NICE group concluded that nicotine does not pose a significant health risk.

Enter MHRA and the European Tobacco Products Directive. The MHRA has

decided to regulate all electronic cigarettes as medicinal products by 2016, and

the European Tobacco Products Directive – currently going through the European

legislative process – proposes that all e-cigarettes should be regulated under

medicines legislation.

‘Smoking cessation’ or ‘smoking sensation’?

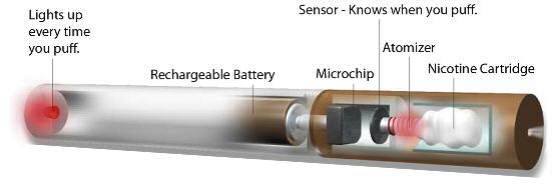

Those in favour of medical regulation argue that electronic cigarettes are currently

unregulated products, that they are accessible to children, that there is no control

over advertising, that they contain potentially dangerous constituents, and that the

devices themselves, including the batteries, pose a threat to user safety.

Medicines regulation, they argue, will improve safety, quality and efficacy, and

make them work better as a smoking cessation product.

There is another thread going through the political argument however, which

is that electronic cigarettes are just another way to feed addiction to nicotine, and

that they send the wrong message and undermine attempts to drive down

tobacco use. Some claim that electronic cigarettes are contrary to efforts to ‘de-

normalise’ smoking. There are already scaremongering stories about

schoolchildren using them. Certainly they might be a short-term fad amongst

some children who wish to challenge authority, but the e-cigarettes market is

made up of long-term smokers and surveys by Action on Smoking and Health

(ASH) show minimal use by non-smokers and by young people.

Consumers do not want medical regulation. There has been extensive

comment on the proposals on social media sites, Twitter, and letters to members

of the European Parliament – current users insist that these are consumer

products, a safe way of enjoying nicotine, rather than a therapy. These products are

popular precisely because they are not medicines. As one user put it – these are

not ‘smoking cessation products’, they are ‘smoking sensation products’.

Getting the balance right

The problem is the trade-off between making the product safe enough, but also

sufficiently attractive to achieve widespread uptake. On balance more weight

should be given to attractiveness, given their relatively low risks and the huge

consequences of continued smoking.

The argument that these products are currently unregulated is false. The

Electronic Cigarette Industry Trade Association has shown that they are covered

by the General Product Safety Directive and various other EC directives covering

electrical safety, chemical safety, weights and measures, packaging and labelling,

commercial selling practice and data protection.

Applications to MHRA are costly, including the licence fee and the required

studies, analyses, documentation. There are fears that few companies will be able

to afford this, that

the process will

favour big players and

drive many products

off the market. There

are further problems

with medical

regulation in that e-

cigarettes include a

big range of products

and product

combinations. Not all

of them are simple

pre-packaged

cigarette lookalikes,

but many are customisable, where the user can vary the delivery device and the

nicotine strength and flavourings. It is likely that medical regulation will

prematurely limit the range of products and stifle innovation.

Even the announcement of future medical regulation has created uncertainty

among retailers, current and potential e-cigarettes users.

How this will play out is uncertain. Given that MHRA has put the deadline as

2016, by then there will be a much larger market and it will be harder to limit and

control products. Already there have been four successful legal challenges against

classing these products as medical products (two in Germany, and one each in

Estonia and the Netherlands).

At the end of the day the potential public health gains from e-cigarettes will

be determined by the decisions about how to regulate these devices. There is

right thinking about tobacco harm reduction, but a risk of making significant

mistakes in the way this is played out in regulatory frameworks.

The danger is a classic regulatory trap: making safer products harder to obtain

than their unsafe counterparts. The regulatory proposals are tougher on e-

cigarettes than on tobacco cigarettes. The framing of electronic cigarettes within

a regulatory context misses the point that the public health drive must be to

promote, endorse and facilitate their use.

DDN

Prof Gerry Stimson is visiting professor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical

Medicine and director of Knowledge-Action-Change.

OR E-CIGARETTES